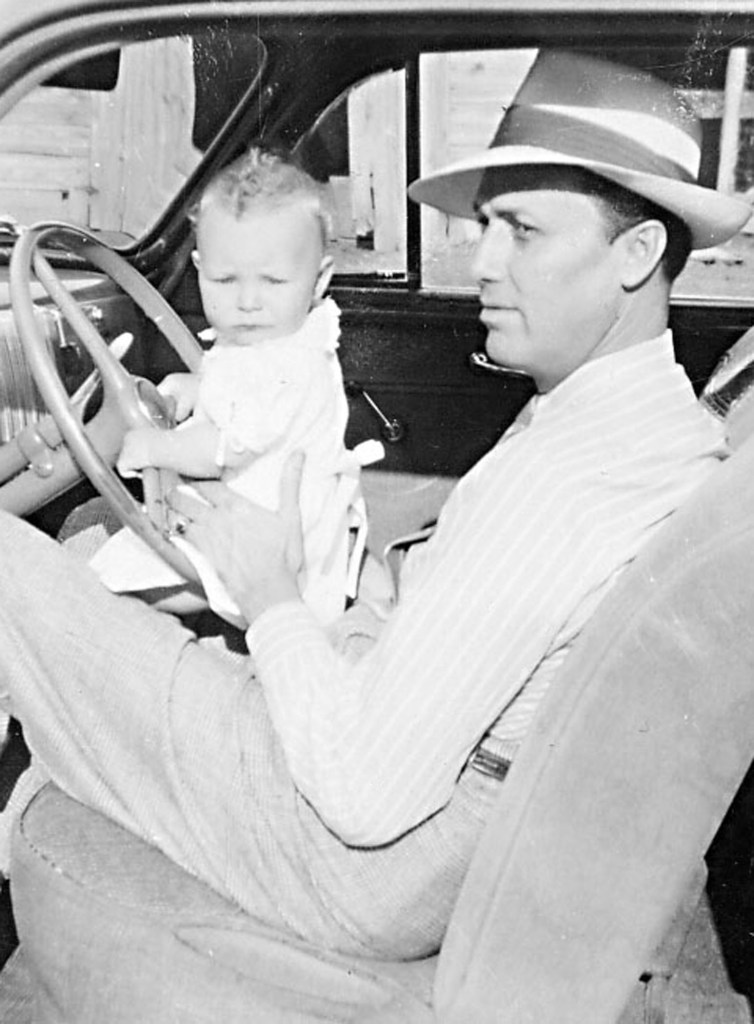

This morning, I was looking for old photos of my dad to share on this Father’s Day when I ran across a piece I wrote about him a few years ago. It seems as good a time as any to return to the blog. Here’s the essay, and Daddy, here’s to you.

The Saturday morning Daddy died, I’d washed my hair, and I was sitting under the dryer when my mother called. It was February, cold but sunny in Jackson, even colder in north Mississippi. Daddy had been raking leaves, she said. Yes, in February; the falling leaves had dwindled to one here and there, but she and I always joked that he had to be there to catch the last leaf when it fell. He knew he had a serious heart issue. My mother and I knew it, too, but she and I had given up policing. “We can’t take everything away from him,” she’d said. And so he still puttered in the yard, played a little golf, and went to the grocery whenever she “needed” something.

When she called, they had already arrived at the local hospital. He’d refused to let her call an ambulance, so she’d driven him, and now he was in what passed for intensive care. “A heart attack,” she said, her voice even but tinged with fear. His condition was too precarious to risk moving him to the medical center twenty miles away. “I think you’d better come.”

A three-hour drive. “I will. I’ll be there as soon as I can.” We hung up. What to do?

Frantic, I took my damp hair down and threw clothes into a bag. My boys were playing at a neighbor’s house. I would call my ex-husband to come get them. Surely he would do that. But before I could call, the phone rang. He was gone.

My first thought was, I didn’t get to say I loved him. But he knew. Surely he knew.

Born the eleventh and last child of a north Mississippi farmer, he claimed he was his mother’s favorite child. When he was old enough to work in the fields with his brothers, she kept him home. After high school he went to live with and work for his older brother. A handsome man, Daddy followed the big bands all over the Southeast and collected a number of lovely girlfriends. The proof is in a packet of photographs of beautiful young women I found in a trunk after he died. When he was thirty, his brother moved back to their hometown, and so did he. There he met my mother, whose best friend’s house was across the street from the service station where Daddy worked. Mother was eighteen and he was thirty-two when they married. I was born three years later, an only child because, he once told somebody who was rude enough to ask, “She’s all in the world we ever wanted.”

He was the epitome of a self-made man. He opened an automobile parts store where he worked long hours six days a week. When he was expecting a parts delivery, he would go early in the morning to take inventory and stock the store. Some summer mornings, I went with him. I loved the tin ceilings, the tall bins of parts, the floors stained with motor oil, the smell of automobile paint. My mother was his bookkeeper, and once I was old enough, I’d walk the quarter mile from school to the store in the afternoons and get a Coke from the machine Daddy kept in the back.

His work ethic was his downfall. He was diagnosed with ventricular fibrillation soon after he retired. Their plans to travel “later” evaporated. His frugal nature was the one serious flaw in his and Mother’s relationship. For years she dreamed of building a house out in the country. They bought the hilltop land and an architect drew plans, but Daddy balked. “What if I die?” he told my mother. “You’ll be alone, living out there.” Not building the house deeply disappointed my mother. Yet they loved each other with a love I envied.

His death stunned me. I had thought we would have more time. We’d talked less in those last years, my visits home a whirlwind of activity focused on my sons. Through my divorce, he was the rock. He mailed my children boxes of dime store trinkets. He sent me checks to help out because he knew money was tight. He sent me valentines and big boxes of fresh-cut greenery at Christmas. Sometimes, nearly forty years after his death, I hear his voice: “Things could always be worse,” he would say when life seemed dark.

A few years after both my parents had died, I dreamed they came to visit me. They drove up in their car, much like they used to, got out, and we had a pleasant few minutes together. I was so happy to see them! They couldn’t stay long, they said. “We just came to make sure you’re doing all right.” In the dream I told them I was, and they got back in their car and left. The dream never recurred, and I don’t believe in ghosts or “visitations” from the dead, but I woke from that dream full of their presence and love.

Sometimes, I’m reminded of him: the smell of pipe tobacco, a certain hymn, my adult sons’ resemblance to him. I’m grateful my sons remember his love, strength, and perseverance. I’m grateful, not the least ashamed, to have been a “Daddy’s girl.” I still am.

A nice tribute to your father! And good to see you back at blogging!

I’ve slowed way down, too. But I do want to start blogging more frequently – once I’m semi-organized after a recent move.

LikeLike

Thanks, Joanne!

LikeLike