People might think of Mississippi and imagine almost tropical weather. Along the coast, that’s true, but in the hills of the north, the winters can be harsh, and it’s not that unusual to see snow. Snow immobilizes us Southerners, but the worst winter weather element is ice.

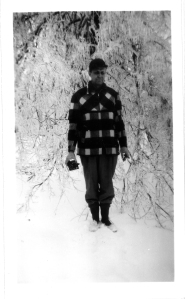

The winter before I turned ten, we had a terrible ice storm. I remember thinking how beautiful it was at first, that fine glazing of everything in a shimmer of ice, but as the ice got heavier and weighed down the trees, some of them bent, and others snapped. So did the power lines. The frightening sound of limbs breaking and big trees coming down went on all night long. We woke to a wonderland of white and crystal, blinding in the sunlight.

We were without power for at least a week, but we were a hardy lot. Or at least, my parents and grandparents were. I remember candles and kerosene lamps, and biscuits and scrambled eggs cooked on top of an oil stove that was our only source of heat.

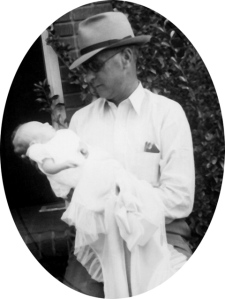

My grandfather’s health was failing by then. I’ve told you that I grew up in a kind of hushed atmosphere because of his illness, and as he grew sicker, there was a pall over that house. My bedroom was next to my grandparents’, and I would hear his coughing all through the night. I still have a vivid image of him, gaunt and frail, propped against pillows, smoking a Lucky Strike, listening to a baseball game on the radio.

The funeral was held at our house. It was what he had wanted; no fine church funeral for him, and there was no funeral home in town. Somebody moved all the living and dining room furniture out except for the piano and brought folding chairs in. In the dining room the casket sat on sawhorses draped in black velvet. It was February, and carnations were the flower of choice. To this day I can’t abide the smell of carnations.

I remember how we stood in the hall, my mother, my grandmother, and I, waiting to go in for the viewing. My heart pounded. I wanted to run. I was ten years old. I could not imagine death. When my grandmother leaned over and kissed my grandfather in his casket, I was astonished. How could she do that? What did it feel like to kiss the dead?

My grandfather became a character in a story about a boy, Jack, whose father deserts the family, and Jack and his mother go to live with the paternal grandfather. The grandfather–Pop–teaches Jack to smoke when he’s thirteen. After that they often smoke together. When Pop is dying, he asks Jack to bring him a cigarette, which creates a dilemma for Jack. It’s against doctor’s orders, but what can it hurt?

Here’s a bit of “Smokers” (the “I” is Jack, the grandson):

I raised all the windows in the room and switched on the attic fan we used only on the hottest nights because Mama complained that it gave her sinus trouble and made Pop’s coughing worse. When I handed him the cigarette, his hands shook so that he dropped it.

“Light it for me, Jack,” he said. “I don’t think I can do it.”

Now that we’d tricked Mama into leaving, I was getting scared. “Pop, I don’t think this is a good idea. Maybe—”

“Please, son. Just light it.”

I had gotten pretty good with practice. The old lighter flicked once, twice, then caught. I lit the cigarette and handed it to him. I had to cup my hands around his to steady it. I was surprised at how deeply he was able to inhale and exhale. Then he held the cigarette himself, balancing it between two fingers of his right hand, almost gracefully. He leaned back, closed his eyes, and let out the longest sigh I ever heard. For one awful moment, I thought he might be dying, but when he opened his eyes, they were light and alive. He wagged the cigarette at me and said, “Don’t you want one?”

“Yes sir. I do.” I lit up, too, and we sat there and smoked together. I watched the clock, and when I figured we had only a few minutes to spare, I pulled the Juicy Fruit from my pocket and took his cigarette and mine outside and crushed them in the dirt under the shrubbery next to the house.

My heart was pounding when I walked back into his room. There was no way that Mama, with her practiced, keen sense of smell, wouldn’t notice cigarette smoke. I stood in the middle of the floor like I’d been nailed to it, not knowing what to do.

What age was a turning point in your awareness of death? Was there a time in your childhood when you felt deeply threatened or frightened? Tell me about it in a comment, or if you don’t want to share, write it down. I believe you’ll be glad you did.

This post is the tenth in a series of memoirs in response to Jane Ann McLachlan’s October Memoir and Backstory Blog Challenge.

Shortly after I graduated high school, death came suddenly for my Carter grandfather. He died of a heart attack at age 79. Three days later his wife, age 73, succumbed to cancer. She had struggled for weeks with the disease, and doctors at the time could do little to improve the quality of life of those suffering the debilitating effects of the disease.

Watching my grandmother wince in silent pain as hospital nurses sought blood veins in her arms and hands to draw blood or to inject saline solutions or pain relievers was something that weighed heavily on my psyche, so much so that I developed a fear of shots. For many years, I could not take a shot sitting or standing up; I needed my feet on plane with my head to avoid fainting. These days, I do okay with shots.

The deaths of my grandparents were the first family deaths, I can recall. My grandparents had moved from Thaxton to Pontotoc three years earlier and were living with us in a house large enough to afford separate living quarters for both families. I’ve never wished them back from the grave, though I regret what I know of them was largely relayed to me via oral tradition.

My desire to write the stories of my life to give to my grandchildren stems from me not having any writings of either of my grandparents. A letter to a relative describing something happening in their life before I was born, who they voted for in a particular presidential election, a short story on subsistence farming…any of these would help me better understand who they were. Instead, I’m left with bits and pieces of the puzzle that was their life; a story relayed by my mother or dad or one of my dad’s siblings, a brace and bit for woodworking, an anvil for blacksmith work, these are touchstones to remind me where I came from and provide insight into who I am.

LikeLike

We were living in Blue Mountain on a dairy farm. With no electricity we have to twice daily milk the cows by hands. It was so cold the cows were not allowed out of the barn, which meant extra feeding and extra shoveling.

It was then I learned that I could shovel (manure), which happened often when ones career was dealing with people’s attitude and actions that were not always pure.

LikeLike

Gerry, that excerpt is beautifully written! Is it published? You are a very talented writer. I want to read the whole story.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jane Ann! “Smokers” isn’t published. It’s something I wrote a long time ago, and it’s an awkward length–@ 12000 words–so it’s long for a story and too short to be a novella. I’m thinking it might be a good NaNoWriMo project–revise and update it, turn it into a YA, maybe.

LikeLike

Gosh Gerry, I really admire how beautifully you draw on your life for your fiction. Isn’t it funny what we remember…carnations…how we associate. Loved reading your memoir and story.

LikeLike

Thanks, Veronica. It is odd, what we remember. I’m remembering much more now than I can possibly write about here.

LikeLike

I remember my grandfather very well, he lived next door and had emphysema. He slept a lot and whenever I was over there, I usually heard “shhhhh Papa’s sleeping”

But every evening I would go over and watch Wyatt Earp with him. He always kept a little clay pot with a lid filled with M&M’s for me.

I still have that little pot. I was 5 when he died.

LikeLike

The only strong positive memory I have of this grandfather is going to a baseball game with him at the local VFW park. It was a night game, and there was a moth in my popcorn. That’s the only thing I remember doing just with him, but it’s vivid.

LikeLike