How do we offer honest, valuable feedback to someone else’s precious, creative work? How do we respond to another person’s writing without a) simply patting the writer on the back and praising the piece, or b) going so negative that the writer wants to rip the story up and never write again? One way is through “reading and responding” to each other’s work. I prefer that phrase to critique; critique sounds so clinical.

I witnessed the worst-case scenario at a prestigious writers’ conference once, where a young workshop participant was so crushed by the craggy, legendary poet’s critique that she packed up and went home. Too sensitive, you say? Maybe. But I believe any criticism that isn’t delivered with integrity and compassion isn’t worth its salt.

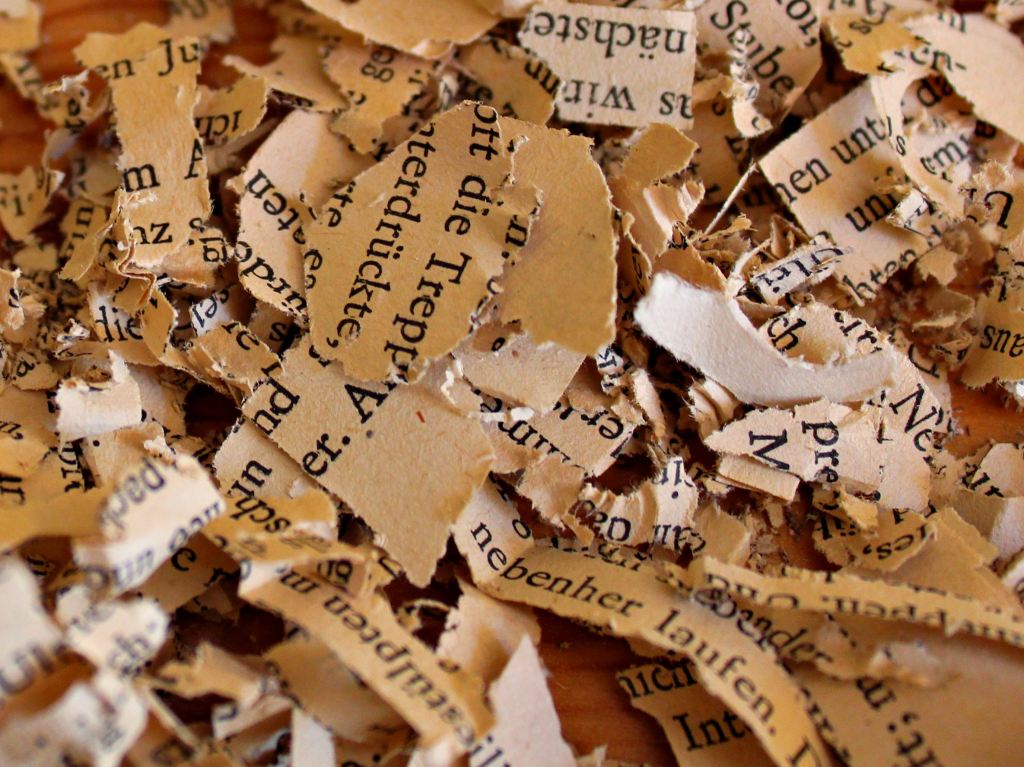

Photo by Evelyn Clement on Unsplash

I learned this lesson the hard way: I taught creative writing to high school students for more than twenty years. Talk about potential for disaster—a room full of teenagers let loose to “critique” each other’s writing! I developed guidelines that work for adults, too.

Many of you are already practiced readers and could offer a tip or two of your own—I hope you will, in the comments—but for those who might not be as familiar with the critique process, here are a few suggestions. None are original to me but common practices I’ve encountered in successful groups.

- Read the piece once without pondering too much. Then read it closely, paying attention to what works and what doesn’t. Consider the elements of craft (I’m focusing on fiction)—plot, characterization, language, setting, opening/ending, etc.—particularly anything the writer has expressed concern about.

- Always, always start by identifying something the writer has done well! No generalizations allowed: no “I really liked it” or “Great job!” Those statements may be true, but they don’t help the writer in concrete ways. Say specifically what you believe worked well: “The dialogue sounds real; I could hear those characters speaking.” “I was intrigued by the plot turn when . . .” “Your setting details establish the mood of the story.”

- Make specific constructive comments. Notice I said constructive, not critical, which means the comments will be useful. Try couching your negatives as questions or “I” statements: “Could you clarify what happens here?” instead of “That’s so confusing.” Or “I didn’t understand when . . .” instead of “You sure lost me!”

Some of you may consider this approach too “touchy-feely.” I’m not saying we can’t offer tough love for a story. We can and should. If all we want is vapid praise, we probably aren’t serious about writing, and we aren’t willing to do the necessary work. Being a good reader requires skill, hard work, and thoughtfulness. It’s a gift we offer to each other.

Remember: as a reader of someone else’s priceless work, be respectful, be honest, be specific, and be constructive!

Let’s talk. Leave a reader tip in the comments to add to the above. I’d love to hear from you!