We talked recently about the importance of ridding a story of whatever isn’t absolutely necessary and/or doesn’t advance the story. This “excess” can be anything from losing a line of description to cutting out a character. Or a scene. In the case of novels, entire chapters.

But once we’ve reduced a story to its bare bones, what’s next?

We look for opportunities.

A few years ago, in a fiction workshop at The Lighthouse Lit Fest in Denver, I had the opportunity to sit down with an author I admired to talk about the opening pages of my novel. That hour was golden, but it was also hard. What I’d thought was a pretty good start had lots of growing to do.

Image: Jan Tenneberg, Unsplash

Most of his comments—scrawled in the margins beside a line or two of underlined text—said simply “Open this door.” He talked about being alert to a range of possibilities to go deeper into a character’s psyche, to make description more visual and significant to the story, to open up the plot in a different direction.

How was it he could see those things when I had not? I’ve decided it’s a skill that comes with practice.

As you read through a draft (preferably aloud), be open to possibilities. Be aware of anything that needles you, of passages that feel somehow incomplete or “off,” of words or phrases that nag you. In my experience, sometimes there’s only a vague uneasiness; I can’t say right away “what’s wrong.” It can feel so urgent to “finish” and get a story out into the world that it’s easy to ignore these signs. Chances are, they won’t go away on their own. And the story won’t fix itself.

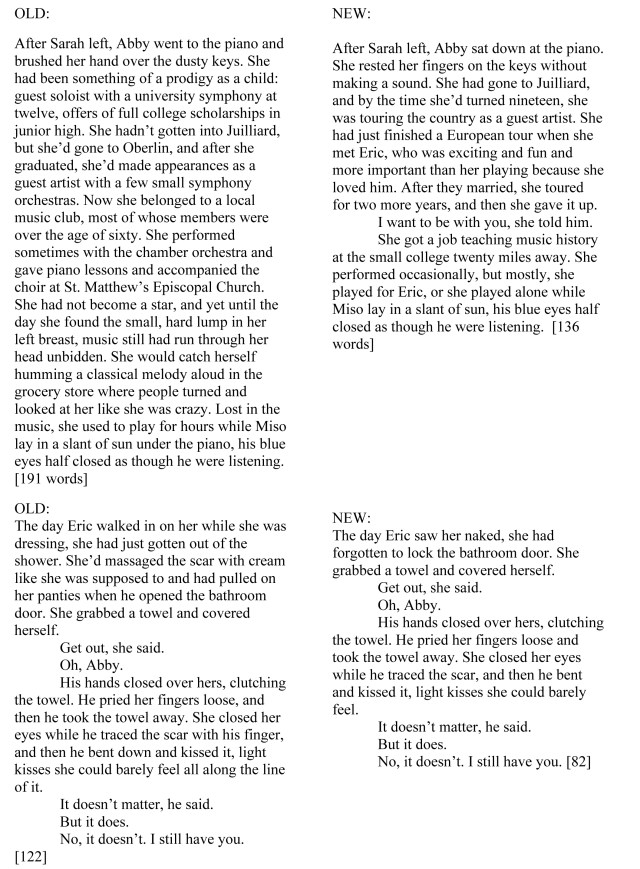

Here’s an example of what I mean by opening doors, taken from a story I’m still working on, “Fast”:

Paul witnessed his father’s hard life as the pastor of two, sometimes three rural churches at a time. His shortest tenure while Paul was growing up was two years, the longest ten; a cycle that repeated throughout his father’s life.

Became this:

Whenever someone asks how he came to be a minister, Paul likes to say he was called. It’s what his father said, and Paul believed it. Why else would a man choose to serve two, sometimes three poor, rural congregations at once, moving every few years to a different set of churches, a different set of people and problems? Paul witnessed the toll it took—never enough energy or time to go around, never enough money. Paul was eighteen and about to leave for college when his father told him he had one piece of advice. He swept his arm around the shabby office in one of those rural churches. “Whatever you do, don’t do this,” he said.

What’s the difference—beyond more words?

What works for you when it comes to “fleshing out” stories? I would love to see your comments.

[This post originally appeared at Story Circle Network, February 10, 2023.]