Today’s Monday Discovery guest writer is Esther Bradley-DeTally, a dynamo-lady who hails from Pasadena, California. Visit her at Sorrygnat, World Citizen. Thanks, Esther, for sharing this excerpt from You Carry the Heavy Stuff.

The best way to describe Esther is to let her do it in her own words:

![q Esther & Puggy[1]](https://gerrygwilson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/q-esther-puggy1.jpg?w=300&h=197)

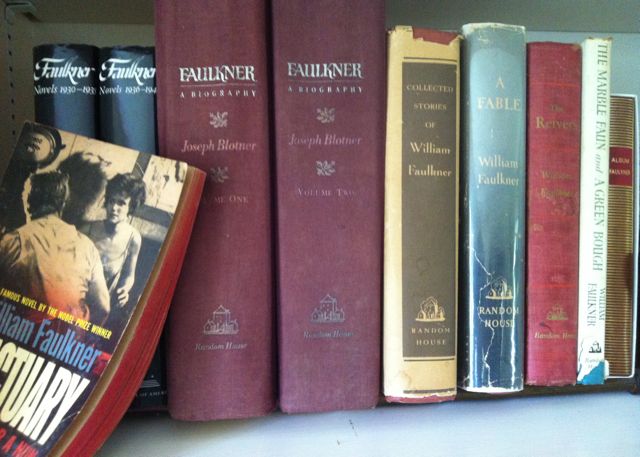

Esther Bradley-DeTally, spirit and writer extraordinaire, and Puggy

.

Just out is The Courage to Write, An Anthology. She is editor of this book and writing teacher to those within its pages. The Courage to Write is published by Falcon Creek Books and is a publication of the Pasadena Public Library, The La Pintoresca branch/Pasadena READS.

Her writing is whimsical, spiritual, serious, laugh out loud funny and offers themes with keen observance of what it means to be human. Someone once said her stuff was “A refreshing read that combines a depth dimension with the tragicomedy that is life.” She is a Baha’i with a passion for making oneness a social reality, fascinated by ordinary people transcending their own inadequacies and limitations in homage to a vision.

She jumps out of airplanes to visit pug dogs, and her best times are with Mr. Bill, her husband and pal extraordinaire, family, and her inner circle of 700 friends.

Being on Watch—Second Bout With Cancer (Spring 2007)

What day do I run to? Does my twin Elizabeth think of this? Her body is a mere cipher. She’s buying the farm. How do I run to her call, “Help me, help me, help me,” which starts just after dawn and carries through the day and night? I jolt out of bed at 5:30 and run into her room, a two-second trip. Early mornings and late evenings require me, her twin. No one else can help at the moment. Bill covers the ritual of medicine doses, and Lindsey and Matthew—her son and his wonderful wife—are going to start staying over.

Liz worries about my dying alone. “Who will you have?” I reassure her, and then I fantasize my demise. I would not realize this was a religious choice reference—that she feared my acceptance of Bahá’u’lláh would hold me back. At the time, I laughed and said, “I’ll be fine.”

An Essay: I Feel It in My Bones

I always said, “I want to go out lying on a huge bed with hundreds of pug dogs over me, as I feebly say, ‘Put the last one on that space over my nose above my lips.’” So under a snuff and snort, I’d end my days. Strange is this getting older. This is going to be an essay. I feel it in my bones. Tonight, my words slough off this day of sitting next to Liz, trying to get hourly liquids into her.

I sit in her kitchen at the computer which makes its “Urr urr” noises, like a new baby. It’s quiet in the kitchen as I reflect on our life as twins. Now, we are beyond the personalities of our twin selves. We are finally down to what really matters. Like Liz, I am waiting to return home, except it’s not my time, and I’m still on earth duty, in dirt city, on Planet Earth. I want to go home to Pasadena.

“What Day Do I Run To?”

Today someone in the writing group posted a question, “What day do I run to?” What does that mean? Then I thought, this is one of my middle-of-the-night questions when I get up and think, when does it end? I, always the frailer twin, have survived heart surgeries and other stuff. It helps at night to sit in her kitchen at the computer and play with writing prompts from our CHPerc site for writers. The basic question is, “Where do I run?” “When do I run out?”

Did I tread the mystical path on practical feet? Did I hoof hard? Was I a solace? Now, it’s  just enough to realize, parts of me are like a big old watch. On what day will I stop ticking? Will it be 2:00 in the afternoon or 2:00 at night? Where will the world be then? Meanwhile, I’m on watch, and I’m writing. Here in Liz’s kitchen on a quiet Idaho night, I think of us, Liz and me. We were the survivors. We’ve always had each other—like book ends. My brother John has been missing for years, and my older sister (Meb, for Mary Ellen Bradley) died at fifty. Liz and I were it.

just enough to realize, parts of me are like a big old watch. On what day will I stop ticking? Will it be 2:00 in the afternoon or 2:00 at night? Where will the world be then? Meanwhile, I’m on watch, and I’m writing. Here in Liz’s kitchen on a quiet Idaho night, I think of us, Liz and me. We were the survivors. We’ve always had each other—like book ends. My brother John has been missing for years, and my older sister (Meb, for Mary Ellen Bradley) died at fifty. Liz and I were it.

A Dvorak Dissonance

Meb was a Girls Latin Scholar and later an unwed mother. “Go tell Dad, he’ll understand” backfired, and she was sent away. She had the baby by herself in Quincy Hospital, but then, as she turned eighteen, she took her baby out of foster care. She married her young love and had three more kids. Her husband left her, so she became a pianist in cocktail lounges. She drank too many drinks offered by grateful customers standing by her piano in a club lounge. Life unraveled, and she ended up on the streets, in housing tenements, dying in a hospital, the same Quincy Hospital where she gave birth. She was alone, poor, alcoholic, and had emphysema. When my twin and I were seventeen, our mom died. I remember Liz and I taking the trolley into downtown Boston and answering the sales lady’s query, “Why do you have to have black dresses?”

My twin is the essence of “don’t tell,” and she never discusses feelings about family. She would tell me during last year’s radiation treatments. When she was ten, standing in our long, graveled driveway, she said to herself, “I’m on my own now. I have to take care of myself.” My mother’s alcoholism had burst out. The Twelve Steps programs were newly emerging, and the doctors would send our mother to a private sanatorium, give her shock treatment. And what about us, Liz and me? She was the sturdy one, good at sports, tree climber par excellence, devotee of “Bobby and the B-Bar Ranch” radio show and “Sgt. Preston” and his dog King. And me—softy, wimp, reader, reader, reader, pathfinder of all the childhood diseases—feeling my mother’s pain. Our early lives had a Dvorak dissonance, later transiting to the spiritual sound of “Coming Home.”

It’s a Symphony, This Life

As I await my twin’s death, I want to tell you it’s a symphony, this life. First, the sacred wounds inflicted upon the soul, and time and twists and colors and sounds, cymbals, drums, some bells and whistles of the funky kind. And the colors—fuchsia, black, gray, stripes of every hue and finally the color blue, a Mediterranean blue—an embracing veil of silken color, obliterating memories of my twin’s despair of my believing in more than Jesus. Also fading are the memories of criticism’s early work. I hope when it comes my time to pass—come to a reckoning, a passage into a final exam, a leap of gladness, the warrior path almost finished—that I be worthy to meet my Creator. I think before I go, I’ll give a final glance at a world back from tilt and furor, and I’ll catch faint sounds of a new symphony, an oratorio, celebrating unity and splendor for the human race.

For thought and action: What day do you run to? Where is your solace? Esther and Gerry would love to have your comments here!

![q Esther & Puggy[1]](https://gerrygwilson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/q-esther-puggy1.jpg?w=300&h=197)