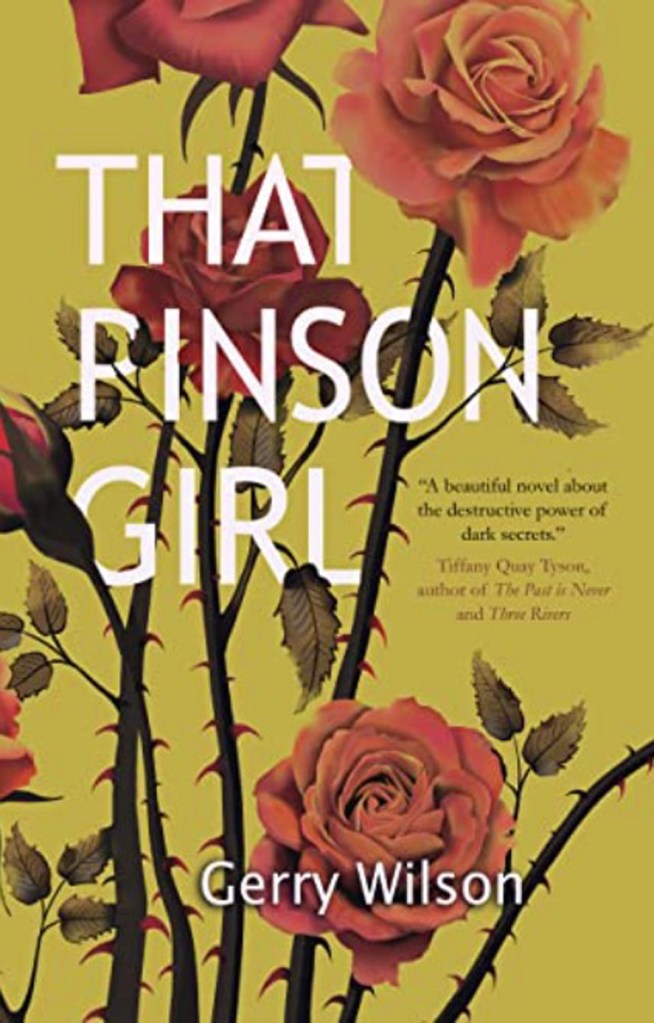

Meet Leona Pinson — “that girl” in That Pinson Girl, my debut novel — who at seventeen gives birth to an illegitimate child. Leona has completed the eighth grade, the only education available to her deep in the beautiful but hardscrabble hills of north Mississippi. Leona lives on a farm with her troubled mother, Rose, her aunt, Sally Pinson (a dwarf whose appearance has always frightened Leona), and her older brother, Raymond, who drinks and rides at night with other young men who feature themselves the “new” Klan. The year before her child is born, Leona’s father died in a hunting accident she believes may have been murder.

Leona is smart and resourceful, but vulnerable. Lying with that boy before he goes off to the war in France and refusing to name him as her son’s father invite the scorn of her family and the community, except for Luther Biggs, a biracial sharecropper who has a long history with the Pinson family. Luther loves and protects Leona, but he too keeps a devastating secret.

Early on, the problematic side of Leona as a character seemed to be that she was a victim of her life circumstances. Nobody wants a passive main character! But as she developed over the course of re-writing the novel many times, I discovered she wasn’t a victim at all, subject to the whims of others and whatever Fate might have in store. She evolved, and eventually, I found depth and resilience and courage in her that surprised me. You see, when Leona encounters hardships — when she walks through the fires of discrimination, hatred, violence, and loss — she suffers, but she picks herself up and gets on with the life she knows, all the while yearning for something better, all the while becoming stronger.

Where does the character of Leona come from?

In part, at least, she comes from me. My own life is probably my deepest source, whether I’m aware of its influences when I’m writing or not. Leona also comes from stories my maternal grandmother told. Her early life was a textbook for living with hardship and loss.

But Leona also comes from this:

When I was a child, a woman lived with her son and her mother in a shabby house down the street from us. It seemed nobody ever visited or called or spoke to them. They went about their lives in isolation. When I asked my parents about them, I got non-answers. I was almost grown when I learned she had borne the son out of wedlock when she was just a girl, and all of them were shunned because of it.

And there you have it: the birth of Leona Pinson as a character. I’m grateful to know her and share her with you.

#

A different version of this piece appeared September 8, 2023, on Substack at Stories I’m Old Enough to Tell. I’m in the process of transitioning this website blog to Substack. I would love it if you would subscribe there (it’s free!) and share with friends.