“We all end up needing thick skin, to an extent, but also need to be able to trade work with peers whose advice we know will push us, in an environment of trust!” —from Elissa Field: comment on Read It and Weep (Not), June 21, 2012

“If you’re like most writers, no single thing will help your writing more than learning to use feedback well.” —Jack Rawlins, The Writer’s Way (emphasis mine)

Today’s post is a follow-up to yesterday’s Read It and Weep (Not) which addressed the role of the reader in sharing writing. We older or more experienced birds who have participated in workshops or swapped our work for a while may have the thicker skin Elissa Field refers to above. I say may have, because I still feel vulnerable when I put my work “out there.”

Let’s assume, though, that the readers of our stories have given their all, and now we, the writers—isn’t it fun to say that?—get to receive comments. Sometimes we receive them in a writers’ workshop where not only do we hear comments, but we may also hear a discussion of the work as though we’re invisible (because in many workshops, that’s our job as writers during the discussion of our work: to be all eyes and ears but remain silent). Most workshop leaders set the tone and establish guidelines for feedback, so generally, it’s a pretty safe place to be, or at least I’ve found it so. Not everyone is so lucky; see my story in the earlier Read It and Weep (Not) post about the poet who left the building.

Squirming in the Spotlight

These days, writers also participate in writing partnerships or groups online where it’s possible to gather in chat rooms, forums, or “Skype” and experience some of the same connections a “live” group has. Whether you’re in a real group or a virtual one, the first order of business for the writer receiving feedback is to be as focused as possible. Here are some tips:

- Listen. Jot down key words or phrases, just enough to remind you later what was said. Why? Because if you’re absorbed in writing down every word, you’ll miss something important. A comment stings? Note it, move on. Don’t let it distract you. Your purpose is to learn as much as you can about what your trusted readers believe is working, what isn’t, and why.

- Bite your tongue! Many workshop leaders will ask writers to be silent until the comments end. Then you can ask questions or re-visit comments if you need clarification. The writer’s instinct is to jump in: “But wait! That’s not what I meant!” Or “You’re completely missing the point. Didn’t you read . . .?” Bite your tongue!

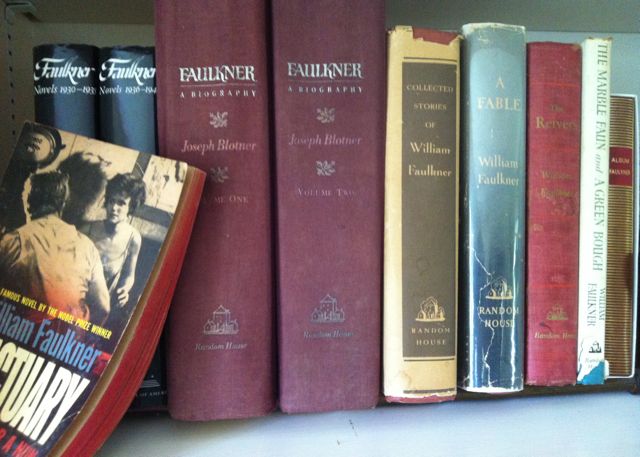

Trendy, Timely Reads

Others exchange work by email, which takes away the face-to-face element but can still be productive. I swap work with a couple of writer-friends I met at workshops whose writing and work ethic I respect.

Let’s say I get a story back, marked up using Microsoft Word’s Track Changes feature (which I personally like; it allows the reader to mark passages and insert comments) and/or with a summary comment of her impressions of the story. I read through it and skim the comments. I try not to “talk back”! I read it again, making my own notes. If I have more than one reader (and I advise you to, if at all possible; it’s helpful), I look for trends. If different readers point out the same issues, then I’d better have a closer look.

Whether you’re working “live” or by email, avoid the pitfalls Jack Rawlins describes in his book, The Writer’s Way.

Don’t be defensive about your work. Deep down, don’t we want to be told the story’s wonderful, don’t change a thing? We need to ask ourselves what we want: to get the pat on the back that’s almost a dismissal, or to make our work the best it can be. We have to be open to honest feedback, or we won’t learn a thing. If additional explanation seems necessary, the story may not be clear. Often, stories are much clearer in our heads than they are on the page. There may be holes we aren’t even aware of.

Come to the writing partnership with questions. What are your issues with the work? Where are you stuck? Where do you have a gut feeling something’s not working? Each writer will have her own issues, and those issues will change from one project to another. Get them out front.

It isn’t the reader’s job to tell you what to do (although with specific problems, she might offer suggestions); the reader’s job is to ask questions of the text and to respond to it with honest insight and knowledge of craft.

Don’t be submissive. The submissive writer wants her readers to “fix it,” or she thinks she has to take advice that goes against her better instincts. Before deciding to follow someone’s advice, put the story away for a while. Then pull it out and ask yourself, “Do I want to do this? Would the story be better for it?” Drop your defenses, but don’t roll over and play dead. Ultimately, the work belongs to you. After careful consideration, decide for yourself which advice to heed and which to ignore.

And finally, a note about your manuscript: make it as clean and error-free as possible. You want your readers to concentrate on substance. It’s not their job to do your proofreading, and a messy manuscript distracts from the main purpose.

Reading and sharing each other’s work is indeed a partnership. At its best, it’s a collaborative effort that makes the work stronger. So be brave. Be open to the possibility for change. Put your work out there!

What are your feelings about receiving feedback? What have you learned that you’d like to pass on to writers who may not have had as much experience as you? Please add your “feedback” in the comments. Let’s continue the conversation!